Letter to James Brooks

Summary

ALS .pp July 16, 1861 James White to James Brooks, July 16, 1861 White writes to inform James Brooks that his son, William, died after an illness of several days. He mentions that the cause of death was probably "conjestion of the brain."

July 16, 1861

Winchester, Va.

My Dear Sir,

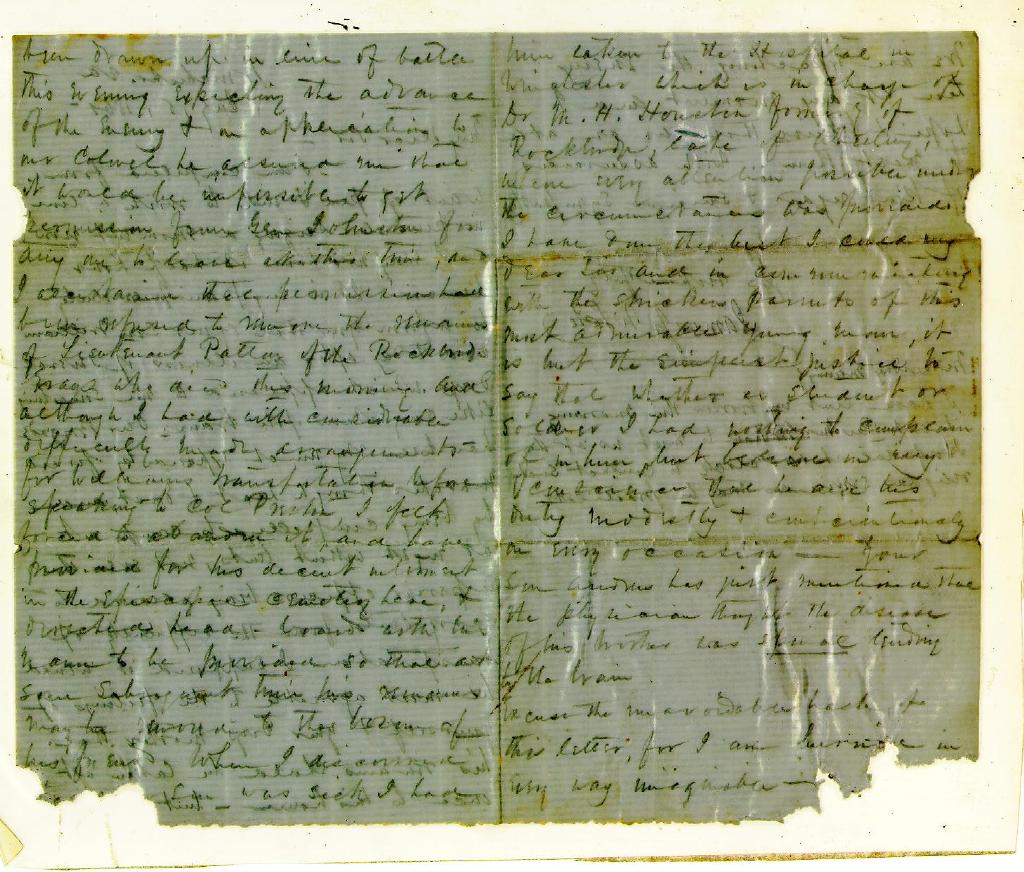

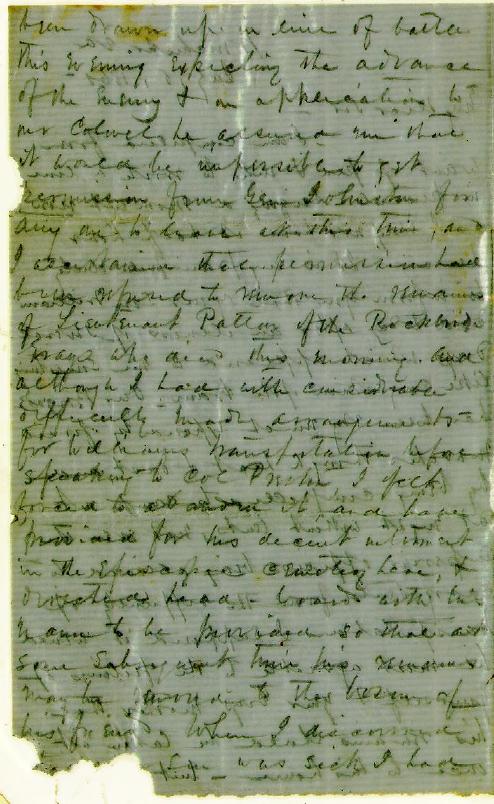

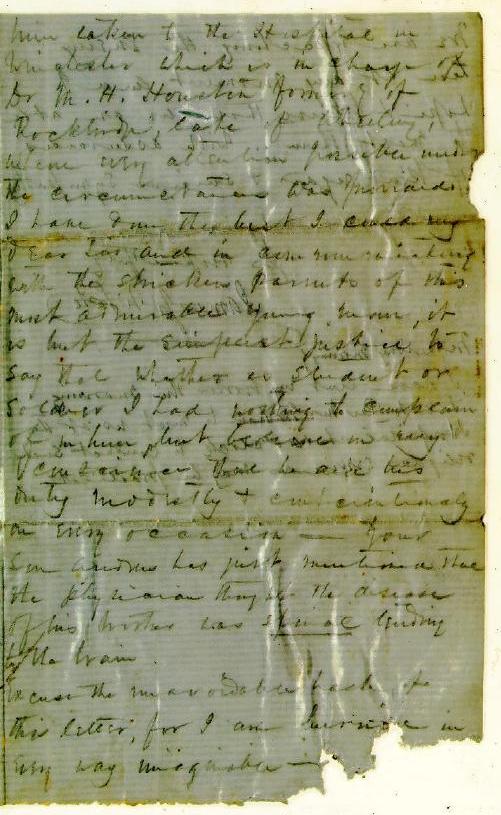

I am compelled from want of pen and ink to write a line in pencil—seizing a moment now I may not have it half hour hence. It is my painful duty to inform you that your son William died today after an illness of several days which appeared to me something like conjestion of the brain. Our brigade has been very much exposed by forced marches through heat and dust, and by being compelled to camp out at night without tents, not even the superior officers being allowed to carry tents from the difficulty of transportation.[1] I suppose it would be most agreeable to the feelings of yourself and your boy's mother that his remains should be taken at once to his home, but we have been drawn up in line of battle this evening[2] and on application to our colonel[3] he assured me that it would be impossible to get permission from Gen. Johnston[4] for any one to leave at this time, and I ascertained that permission had been refused to remove the remains of Lieutenant Patton[5] of the Rockbridge Grays who died this morning. And although I had with considerable difficulty made arrangements for William's transportation before speaking to Col. Preston, I felt forced to abandon it, and have provided for his decent interment in the Episcopal Cemetery here and have directed a head board with his name to be provided so that at some subsequent time his remains may be removed to the bosom of his friends. When I discovered that William was sick I had him taken to the Hospital in Winchester which is in Charge of M. H. Houston, formerly of Rockbridge, late of Wheeling, where every attention possible under the circumstances was provided. I have done the best I could my dear Sir and in communicating with the stricken parents of the most admirable young man, it is but the simplest justice to say that whether as student or soldier, I had nothing to complain of him, but believe in my conscience that he did his duty modestly and conscientiously on every occasion. Your son Andrew has just mentioned that the physician thought the disease of his brother was spinal [unclear]to the brain.[6] Excuse the unavoidable haste of this letter, for I am hurried in every way imaginable. We are expecting the enemy here at any moment and I believe that we are able to meet them. With assurances of kind regards and sincere sympathy.

yours respectfully,

James J. White

Post Script Monday Morning: I have sent my brother [7] this morning to ask Rev. Mr. Graham to meet us at the Hospital at 10:00 o'clock to conduct such religious service as may be practicable.

Footnotes

- 1

Colonel Thomas Jackson was the officer in charge of the Virginia troops who gathered in the Valley in late spring/early summer of 1861. Not only did the soliders endure grueling drills, but they did not have adequate supplies—particlarly clothing and tents—which led to widespread sickness among the regiments (Robertson, Fourth Virginia Infantry, 3-4).

- 2

Here White refers to the impending First Battle of Manassas. On July 18, the troops were ordered to abandon Winchester and head east across the Blue Ridge Mountains. On Sunday, July 21, Jackson's troops engaged the Federals at Manassas (Robertson, Fourth Virginia Infantry, 5-7).

- 3

Colonel James F. Preston was in charge of the Fourth Virginia Infantry when it was organized. However, his poor health kept him in Richmond while his troops were drilling in the Valley. Wounded at First Manassas, he later died in January, 1862 at home (Robertson, Fourth Virginia Infantry, 2, 68).

- 4

General Joseph E. Johnston (1807-1891) received his diploma from the U. S. Miltary Academy in 1829 along with his friend Robert E. Lee. He received praise for his service in both the Mexican War and in the wars against the Seminole Indians. In April of 1861, he resigned from his position as a brigadier general in the U. S. Army, and in May of 1861 accepted a commission as a brigadier general in the Confederate Army. He commanded the Army of the Shenandoah at Harper's Ferry and led Confederate forces at First Manassas, August 1861 (McMurry, 859-61).

- 5

William Patton, a merchant, had joined the Rockbrige Grays (Company H) as Second Lieutenant in April of 1861. Like William Brooks, he died on July 16 of 1861 at Winchester. His remains are now buried at Timber Ridge Presbyterian Church in Rockbridge County (Robertson, Fourth Virginia Infantry, 67).

- 6

See Andrew's letter to his mother of July 16, 1861, reporting that William is very ill.

- 7

Hugh Augustus White (1840-1862), whose brother James was Company I's first captain, enlisted in the 4th Virginia Infantry while a student at Washington College. On September 13, 1861, Hugh White was named sergeant, and on April 21, 1862, he was elected captain. Surprised that he was elected captain, Hugh White accepted the position with a great sense of responsibility. As he wrote to his brother Henry, "Promotion in itself brings neither peace nor happiness, and unless it increases one's usefulness it is a curse. An opportunity is now afforded for exercising a wider influence for good, and if enabled to improve this aright I shall then be happier than before" (quoted by Bean, 111). White was killed on August 30, 1862 at Second Manassas (Robertson, 4th Virginia Infantry, 80).